January 09, 2026 Procurement Insights

Why Mid-Production Specification Changes Trigger Quality Control Revalidation in Custom Drinkware Orders

Overview

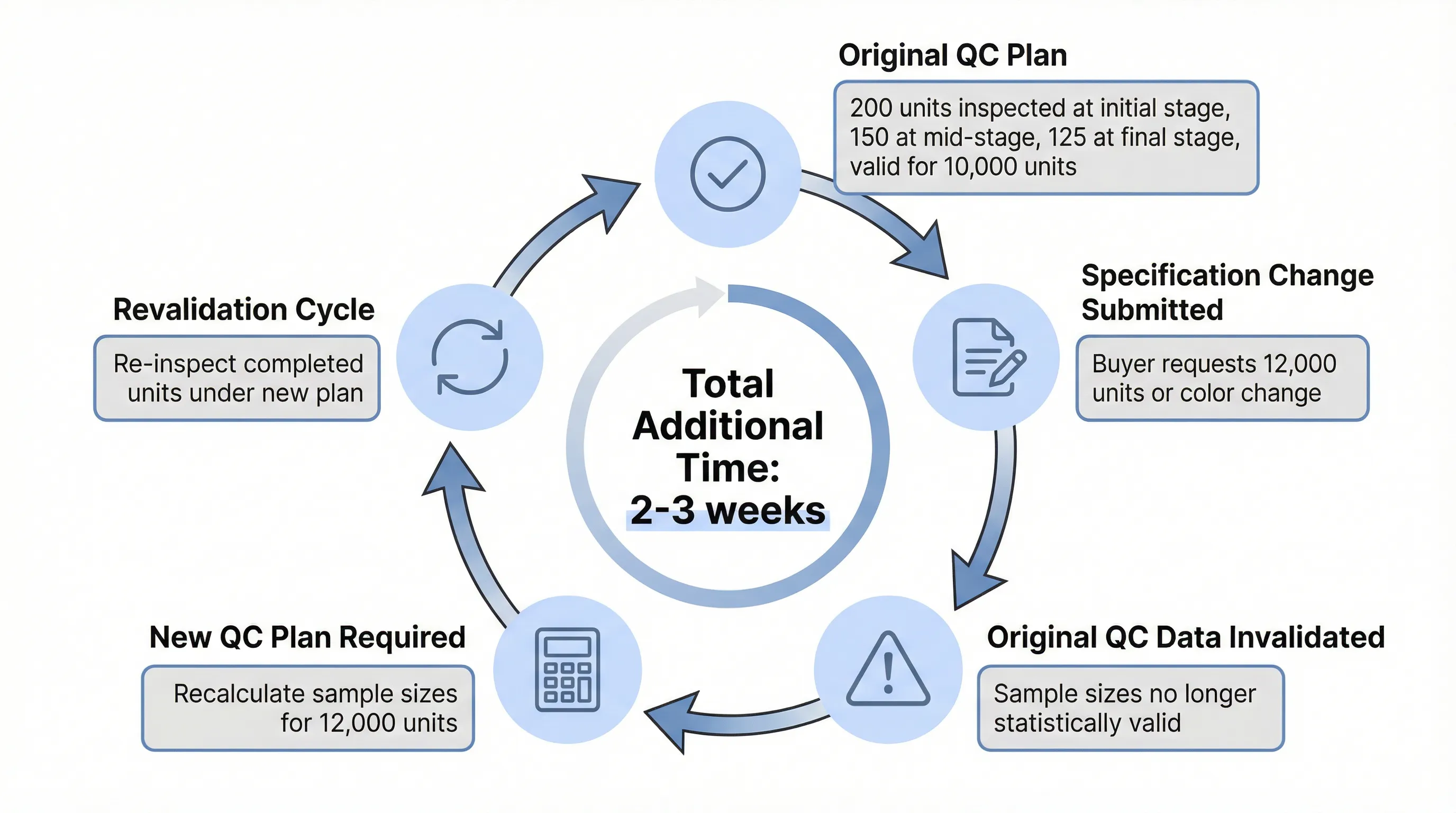

Quality control consultants explain why requesting quantity increases or color changes after production begins invalidates statistical sampling plans and triggers a complete revalidation cycle that extends lead times by 2-3 weeks.

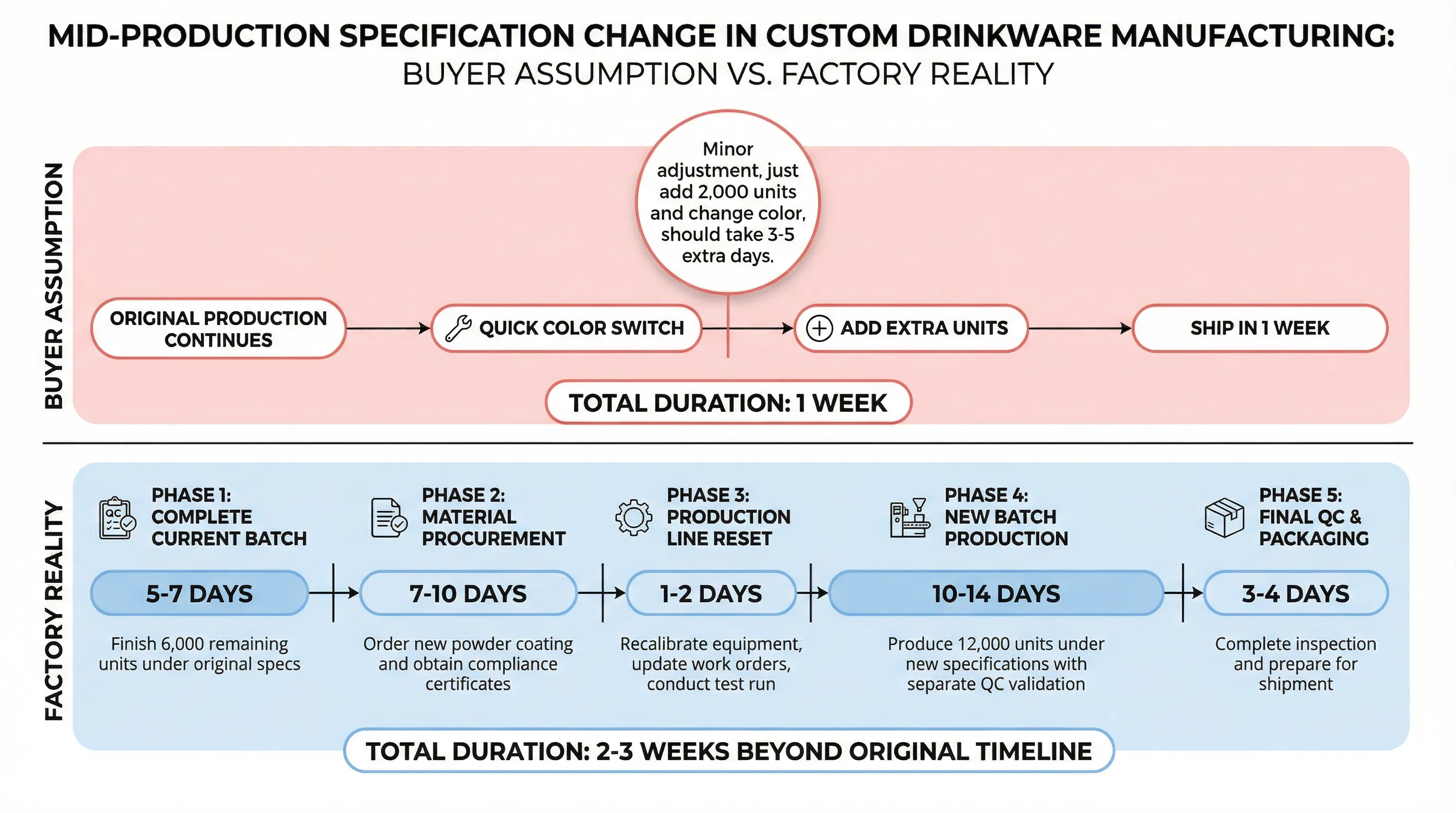

When procurement teams submit order specification changes during the production phase—requesting a quantity increase from 10,000 to 12,000 units, or switching from matte black to glossy white powder coating—they typically frame these as "minor adjustments" that should require minimal additional time. The assumption is that the factory can simply extend the current production run to accommodate the extra units, or make a quick modification to the coating process for the color change. In practice, this is often where lead time estimates for custom drinkware orders start to diverge significantly from buyer expectations. What appears to be a straightforward modification on a purchase order triggers a complete quality control revalidation cycle on the factory floor, because production validation protocols are designed around specification-locked parameters that cannot be altered mid-stream without invalidating the entire quality assurance framework. The additional lead time required for this revalidation—typically two to three weeks—is rarely factored into the buyer's delivery expectations, because the decision to modify specifications is made after the production timeline has already been communicated and the factory has committed resources to the original order parameters.

The core issue is not that factories are inflexible or that quality control processes are unnecessarily rigid. The problem lies in how mid-production specification changes affect the statistical validity of quality control sampling plans that have already been executed. When a factory begins production on a 10,000-unit order of custom stainless steel water bottles, the quality control team designs a sampling plan based on internationally recognized standards such as ISO 2859-1, which specifies the number of units to be inspected at each production stage based on the total batch size and the acceptable quality limit. For a 10,000-unit order, the sampling plan might require inspection of 200 units at the initial production stage, 150 units at the mid-production checkpoint, and 125 units at the final inspection stage. These sample sizes are calculated to provide a statistically valid representation of the entire batch, ensuring that if the sampled units meet quality standards, the entire 10,000-unit batch can be confidently released for delivery. However, when the buyer requests a quantity increase to 12,000 units after 4,000 units have already been produced and inspected, the factory cannot simply add 2,000 more units to the existing batch and continue production. The sampling plan that was valid for 10,000 units is no longer statistically valid for 12,000 units, because the sample size must be recalculated based on the new batch total. This means the factory must either re-inspect the 4,000 units that have already been produced using the new sampling plan, or treat the additional 2,000 units as a separate batch with its own independent sampling plan. Either approach requires additional quality control resources and extends the production timeline, because the factory cannot release any units for delivery until the entire 12,000-unit order has been validated under a consistent quality control framework.

The situation becomes more complex when the specification change involves a modification to the product itself, rather than just a quantity adjustment. When a buyer requests a color change from matte black to glossy white after production has started, the factory faces a fundamentally different challenge. Powder coating is not a process that can be easily reversed or modified mid-batch. The 4,000 units that have already been coated in matte black cannot be re-coated in glossy white without stripping the existing coating, which would damage the underlying stainless steel surface and compromise the structural integrity of the bottles. This means the factory must complete the remaining 6,000 units of the original 10,000-unit order using the matte black coating, and then start a new production run for the 12,000-unit order with glossy white coating. The buyer may assume that the factory can simply switch the coating color for the remaining 6,000 units and add 2,000 more, but this assumption fails to account for the fact that material procurement is batch-specific. The factory has already ordered the exact quantity of matte black powder coating required for 10,000 units, based on the original purchase order. Switching to glossy white mid-production would require the factory to order a new batch of glossy white powder coating, which suppliers typically sell in minimum order quantities that far exceed the 6,000 units remaining in the current batch. The factory would need to order enough glossy white powder coating for at least 10,000 units to meet the supplier's minimum order quantity, which means the buyer would be paying for material that will not be used in this order. Alternatively, the factory could complete the current 10,000-unit order in matte black as originally specified, and then start a completely new 12,000-unit order in glossy white, which would require a separate production timeline and a separate quality control validation cycle.

The quality control revalidation requirement becomes even more stringent when the specification change involves a modification to product dimensions or branding elements. When a buyer requests a 20% increase in logo engraving size after production has started, the factory cannot simply adjust the engraving template and continue production. Laser engraving is a precision process that requires calibration based on the exact dimensions and placement of the logo on the bottle surface. The engraving depth, laser power, and engraving speed are all calibrated to produce a logo of a specific size and clarity. Increasing the logo size by 20% requires recalibrating the laser engraving equipment, which in turn requires producing new test samples to verify that the larger logo meets the buyer's quality expectations. These test samples must be produced, inspected, and approved by the buyer before the factory can proceed with engraving the larger logo on the remaining units. If the buyer is located in New Zealand and the factory is in China, this approval process can add five to seven days to the production timeline, because the test samples must be photographed, the images must be sent to the buyer for review, and the buyer must provide written approval before production can resume. During this approval window, the production line cannot continue engraving bottles, because proceeding without approval would risk producing thousands of units with a logo size that the buyer ultimately rejects. The factory must either pause the engraving process and move the production line to a different order, or keep the line idle until approval is received. Either option extends the lead time, because pausing and resuming production requires additional setup time, and keeping the line idle means the factory is not making progress on the buyer's order.

The material procurement implications of mid-production specification changes are often underestimated by buyers, because they assume that factories maintain large inventories of raw materials that can be easily substituted or reallocated to accommodate order modifications. In reality, most custom drinkware factories operate on a just-in-time procurement model, where materials are ordered in quantities that precisely match the specifications of confirmed purchase orders. When a factory receives a purchase order for 10,000 matte black stainless steel water bottles, the procurement team orders exactly 10,000 bottle bodies, 10,000 lids, 10,000 silicone seals, and the exact quantity of matte black powder coating required to coat 10,000 units, with a small buffer (typically 2-3%) to account for production waste. This procurement approach minimizes inventory holding costs and reduces the risk of obsolete materials sitting in the warehouse. However, it also means that when a buyer requests a specification change, the factory cannot simply pull materials from existing inventory to accommodate the modification. If the buyer requests a color change to glossy white, the factory must place a new order with the powder coating supplier, which typically requires a lead time of seven to ten days for delivery. During this period, the factory cannot proceed with coating the bottles, because the glossy white powder coating has not yet arrived. The factory could theoretically continue producing bottle bodies and lids while waiting for the new coating to arrive, but this creates a logistical challenge, because the partially completed units must be stored somewhere on the factory floor without interfering with other production runs. Most factories do not have unlimited storage space, so holding partially completed units for an extended period can disrupt the production schedule for other orders.

The regulatory compliance implications of specification changes are particularly significant for food-grade drinkware products sold in markets with strict safety standards, such as New Zealand, Australia, and the European Union. When a factory produces custom stainless steel water bottles for the New Zealand market, the bottles must comply with the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, which specifies requirements for materials that come into contact with food and beverages. The factory must provide material certificates confirming that the stainless steel used in the bottle bodies is food-grade 304 stainless steel, and that the powder coating used on the exterior surface does not contain heavy metals or other substances that could leach into beverages. These material certificates are issued by the raw material suppliers and are specific to each batch of materials procured for a particular order. When a buyer requests a color change from matte black to glossy white, the factory must obtain new material certificates for the glossy white powder coating, because the chemical composition of the glossy white coating may differ from the matte black coating, even if both are food-safe. Obtaining these certificates typically requires submitting a request to the powder coating supplier, who must then provide documentation confirming that the glossy white coating complies with the relevant food safety standards. This documentation process can add three to five days to the production timeline, because the factory cannot proceed with coating the bottles until the material certificates have been received and verified. If the powder coating supplier is unable to provide the required certificates, the factory must find an alternative supplier who can provide both the glossy white coating and the necessary compliance documentation, which can extend the lead time by an additional one to two weeks.

The production line setup implications of specification changes are often invisible to buyers, because they occur behind the scenes on the factory floor and are not reflected in the external communication between the buyer and the factory's sales team. When a factory sets up a production line to manufacture 10,000 custom water bottles, the setup process involves configuring multiple workstations to handle specific tasks in sequence: bottle body forming, lid assembly, powder coating, laser engraving, quality inspection, and packaging. Each workstation is optimized for the specific parameters of the order, such as the bottle size, the coating color, the logo dimensions, and the packaging configuration. The operators at each workstation are trained to perform their tasks according to the specifications documented in the production work order, which serves as the authoritative reference for how each unit should be produced. When a specification change is submitted mid-production, the factory cannot simply update the work order and expect the operators to adjust their processes on the fly. The production line must be paused, the work order must be revised to reflect the new specifications, and the operators must be re-briefed on the changes. This re-briefing process is not a formality—it is a critical step in ensuring that the specification change is implemented correctly and consistently across all workstations. If the logo size is being increased by 20%, the engraving operator must understand the new dimensions, the new placement on the bottle surface, and the new laser settings required to achieve the desired engraving depth and clarity. If this information is not communicated clearly, the operator may continue engraving logos at the original size, resulting in thousands of units that do not meet the buyer's updated specifications. To prevent this type of error, factories typically require a production line reset when a specification change is submitted, which involves stopping production, updating all work orders and training materials, conducting a test run with the new specifications, and obtaining approval from the quality control team before resuming full-scale production. This reset process typically takes one to two days, which may seem minor in isolation, but when combined with the material procurement delays, the quality control revalidation cycle, and the regulatory compliance documentation requirements, the cumulative impact on lead time can reach two to three weeks.

The practical consequence for buyers is that requesting mid-production specification changes after the production timeline has been agreed upon introduces a lead time extension that was not accounted for in the original delivery schedule. If the buyer communicated the specification change at the time of order placement, the factory could have built the additional time into the production schedule and coordinated material procurement, quality control planning, and production line setup to accommodate the buyer's requirements from the outset. However, when the specification change is submitted after production has started—often during the quality control phase, when the buyer reviews progress photos and decides they want to modify the logo size or change the color—the factory must manage the change as a disruption to an already-optimized production workflow. This disruption is not a matter of the factory being uncooperative or inflexible. It is a reflection of the fact that production validation protocols are designed to ensure consistent quality across an entire batch, and any change to the specifications requires re-validating the quality control framework to maintain that consistency. For buyers who require delivery by a specific date to support a corporate event, a product launch, or a seasonal marketing campaign, this two-to-three-week delay can be the difference between receiving the bottles in time for the event and having to postpone or cancel the distribution. The most effective strategy for buyers who anticipate the possibility of specification changes is to communicate those potential changes at the time of order placement, rather than waiting until production is underway. If the buyer is uncertain about the final logo size or the final color choice, it is better to delay the start of production by a few days to finalize those decisions, rather than starting production with provisional specifications and then requesting changes later. Early communication allows the factory to coordinate material procurement, quality control planning, and production line setup in a way that accommodates the buyer's requirements without triggering a disruptive revalidation cycle. For buyers who understand [how production timelines are structured](/blog/custom-drinkware-production-lead-time-new-zealand) around specification-locked validation protocols, the decision to finalize specifications before production begins becomes a strategic priority, because it eliminates the risk of mid-production delays that could jeopardize the delivery schedule and the success of the buyer's distribution plans.