January 13, 2026 Lead Time

Why Order Quantity Tier Changes Trigger Production Line Rebalancing in Custom Drinkware Manufacturing

Overview

Buyers assume increasing order quantities from 5,000 to 10,000 units is simple arithmetic. In reality, quantity tier changes trigger a complete production line rebalancing cycle extending lead times by 1-2 weeks.

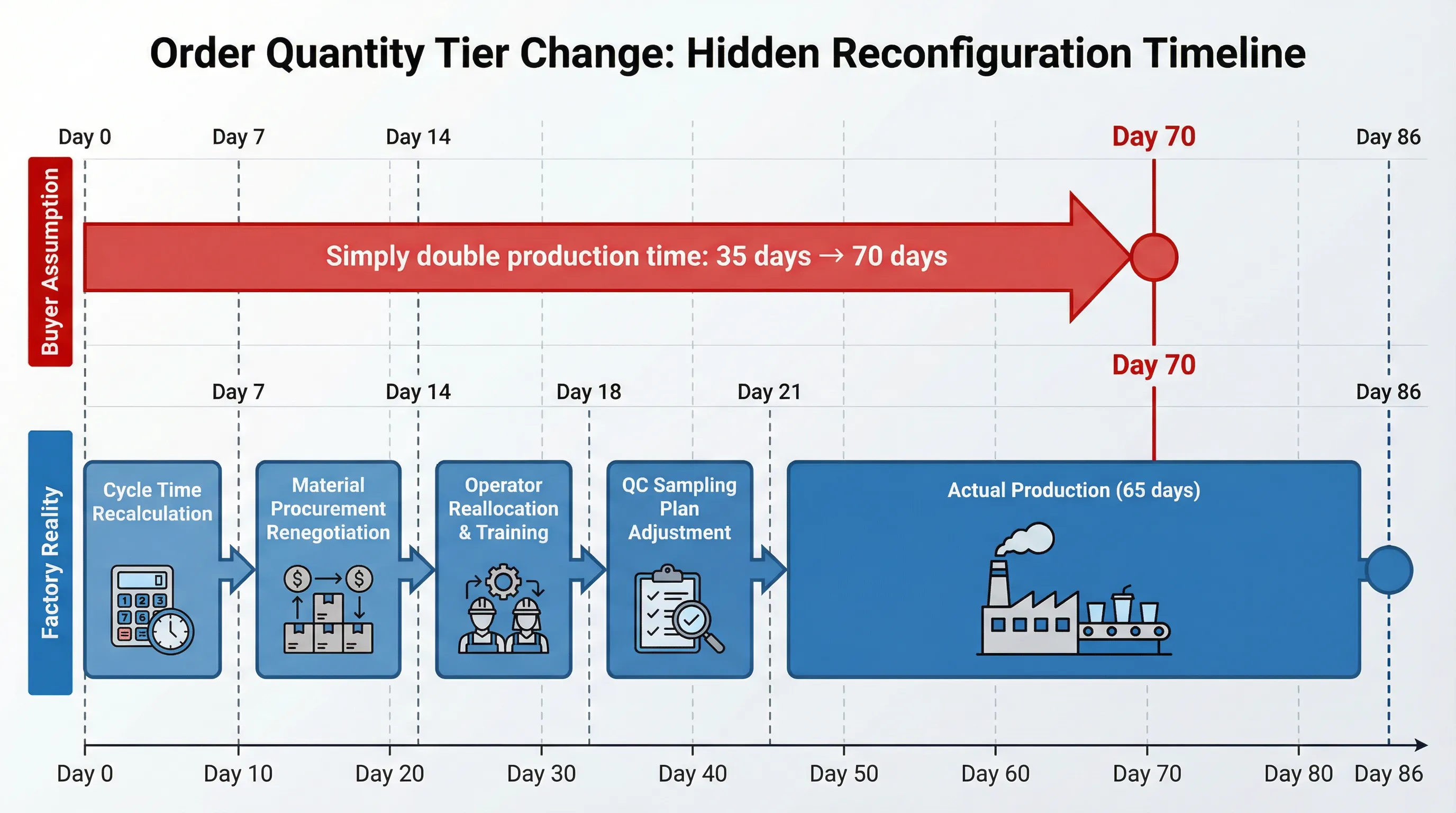

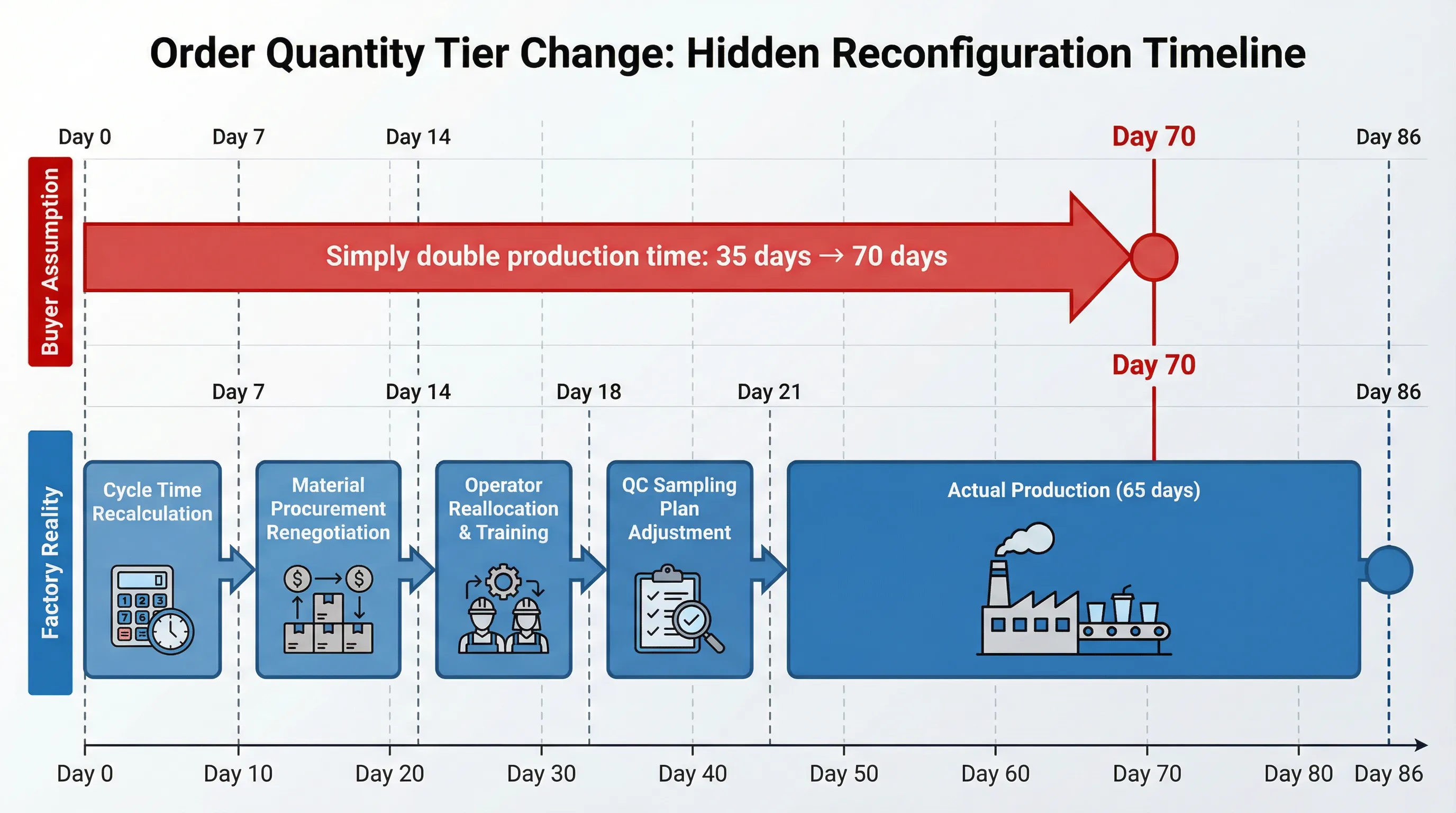

When procurement teams receive a quotation for 5,000 custom stainless steel water bottles with a 35-day production timeline, they often approach quantity planning with a straightforward assumption: if 5,000 units require 35 days, then doubling the order to 10,000 units should require approximately 70 days, perhaps with a modest efficiency discount bringing the timeline down to 60 or 65 days. The calculation appears logical—more units simply mean more production time, scaled proportionally. In practice, this is often where lead time projections for quantity tier changes start to diverge from the factory's actual timeline requirements. What appears to be a simple arithmetic adjustment—increasing the order quantity from one tier to another—triggers a comprehensive production line rebalancing cycle that factories must complete before they can commit to a revised delivery schedule. The additional timeline required for this rebalancing, typically ranging from seven to fourteen days depending on the magnitude of the quantity change, is rarely communicated explicitly in revised quotations, because factories quote lead times assuming that the production configuration has already been optimized for the specified quantity. The disconnect between the buyer's linear scaling assumption and the factory's workflow reconfiguration reality creates a hidden delay window that compounds when buyers are working backward from fixed launch dates or seasonal deadlines.

The core issue is not that factories are being inefficient or deliberately extending timelines. The problem lies in how production line optimization operates at different batch size thresholds. When a factory receives a request to increase an order from 5,000 units to 10,000 units, the production planning team cannot simply extend the existing production schedule by adding more days to the calendar. The production line configuration that was optimized for a 5,000-unit batch—the number of workstations, the allocation of operators across those workstations, the cycle time for each assembly step, the material procurement batch sizes—was designed to maximize efficiency for that specific quantity tier. Increasing the quantity to 10,000 units shifts the production into a different efficiency threshold, where the optimal configuration requires a different balance of labor, machinery, and material flow. This reconfiguration is not optional—it directly determines whether the factory can produce the increased quantity without creating bottlenecks, idle time, or quality control failures. For buyers who have never worked through a quantity tier change with a factory before, or who assume that production scaling is purely additive, this rebalancing cycle can extend the timeline by one to two weeks before the revised production schedule can even be finalized, let alone executed.

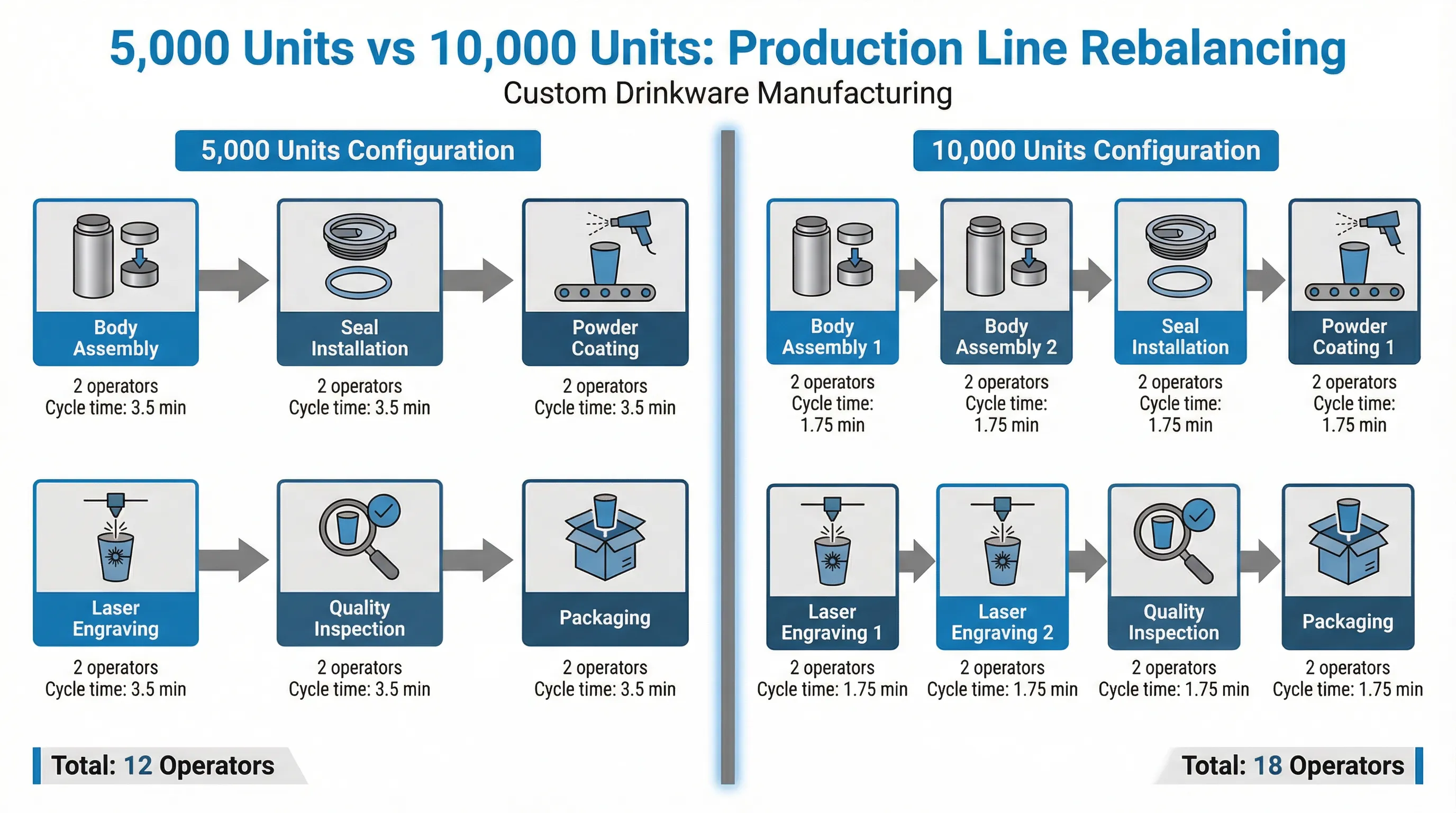

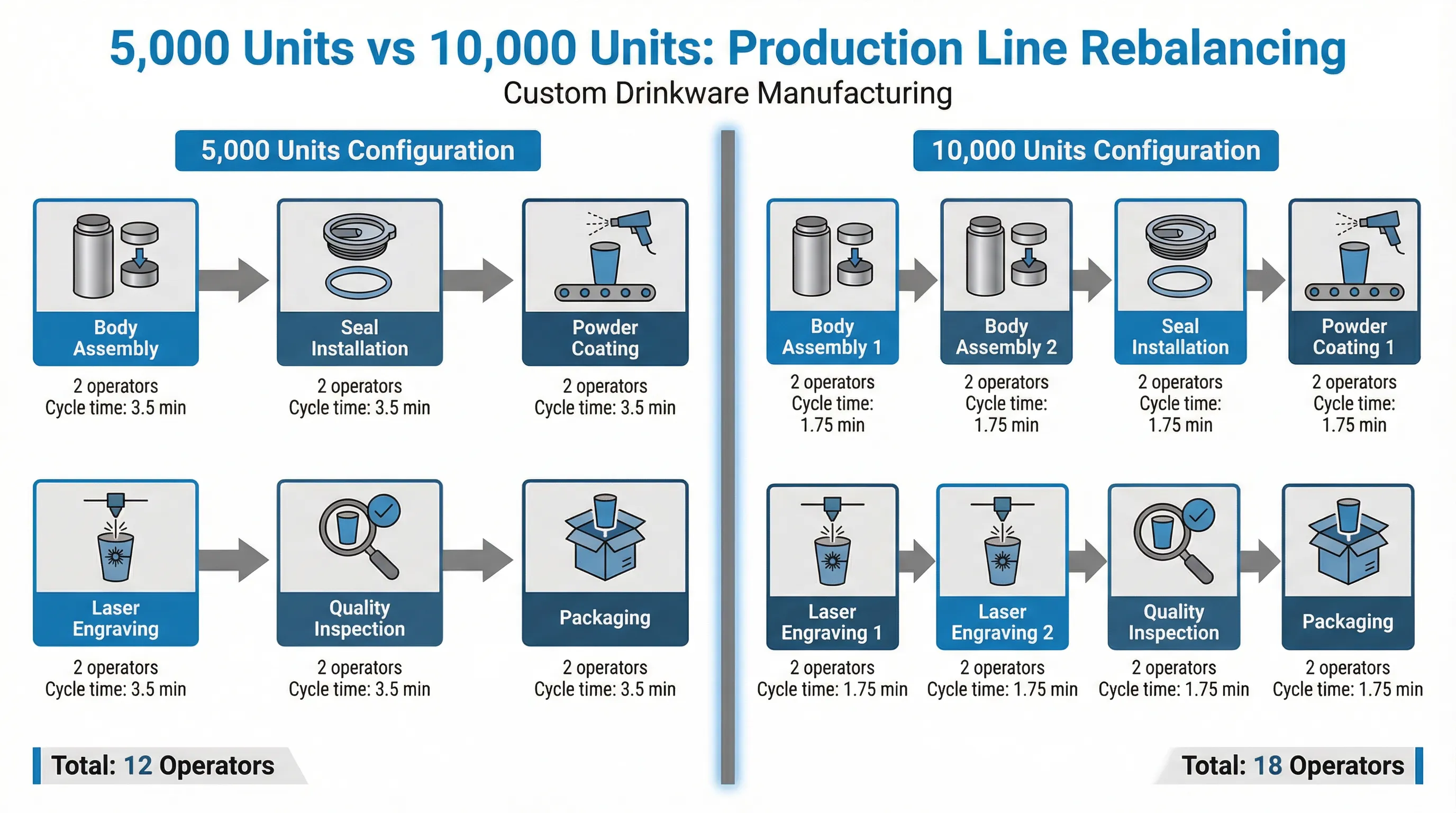

The production line balancing calculation itself introduces the first layer of complexity that buyers often underestimate. When a factory designs a production line for 5,000 custom water bottles, the production planning team calculates the cycle time—the maximum duration that each workstation can take to complete its assigned tasks without creating a bottleneck in the overall flow. This cycle time is derived by dividing the total available production time by the required number of units. For a 5,000-unit order with 30 days of available production time (assuming 8-hour shifts and 22 working days per month), the cycle time might be calculated as 3.5 minutes per unit. The factory then distributes assembly tasks across workstations to ensure that no single station exceeds this 3.5-minute threshold. One workstation might handle body assembly and seal installation, another handles powder coating preparation, another handles laser engraving, and another handles final inspection and packaging. Each station is staffed with the appropriate number of operators to complete its tasks within the 3.5-minute cycle time. This configuration works efficiently for 5,000 units because the workload is balanced—no station is significantly faster or slower than the others, which minimizes idle time and maximizes throughput.

When the buyer requests an increase to 10,000 units, the factory cannot simply run the existing production line for twice as long. The cycle time calculation changes fundamentally. If the factory attempts to produce 10,000 units using the same 30-day production window, the required cycle time drops to 1.75 minutes per unit—exactly half of the original cycle time. This faster pace means that every workstation must complete its tasks in half the time, which is not achievable with the current operator allocation and workstation configuration. The body assembly station that previously had two operators working at a comfortable pace to complete tasks in 3.5 minutes cannot simply work twice as fast—human labor does not scale linearly in that manner. The factory must instead reconfigure the production line by adding more workstations, reallocating operators, and redistributing tasks to ensure that each station can meet the new 1.75-minute cycle time without compromising quality or creating excessive operator fatigue. This reconfiguration process is not instantaneous—it requires the production planning team to recalculate task distributions, test the new configuration with trial runs, and adjust operator training to ensure that everyone understands their revised responsibilities.

The material procurement timeline adds another layer of complexity that buyers rarely account for when requesting quantity increases. Factories do not maintain unlimited inventories of raw materials for custom orders, because the specifications vary significantly between buyers and the capital cost of holding excess inventory is prohibitive. When a factory receives an order for 5,000 custom water bottles, the procurement team places orders with material suppliers for the specific quantities required: 5,000 stainless steel bodies, 5,000 silicone seals, 5,000 powder coating portions, and 5,000 sets of packaging materials. Material suppliers, in turn, optimize their own production and delivery schedules based on the quantities ordered by the factory. A supplier might batch multiple small orders together to achieve economies of scale, or they might schedule delivery based on their own production capacity constraints. When the factory requests a quantity increase to 10,000 units, the procurement team must renegotiate with material suppliers to secure the additional materials. This renegotiation is not a simple matter of doubling the order—suppliers have their own minimum batch sizes, lead times, and capacity constraints that may not align with the factory's revised timeline. A powder coating supplier who previously agreed to deliver 5,000 portions in two weeks might require three weeks to deliver 10,000 portions, because the larger quantity exceeds their standard batch size and requires additional production runs. The factory cannot begin the reconfigured production line until all materials are confirmed to be available, which means the material procurement renegotiation timeline must be completed before the production line rebalancing can even be finalized.

The operator reallocation process reveals the most significant difference between how factories handle quantity increases at different batch size thresholds. Production lines are staffed based on the workload requirements for a specific quantity tier. A 5,000-unit production run might require twelve operators distributed across six workstations, with each operator trained to handle specific tasks within their assigned station. When the quantity increases to 10,000 units, the factory must determine whether the existing twelve operators can handle the increased workload through extended shifts, or whether additional operators must be recruited and trained. Extended shifts are not always a viable solution—labor regulations, operator fatigue, and quality control standards impose limits on how many hours operators can work consecutively without compromising performance. If the factory determines that additional operators are needed, the recruitment and training timeline must be factored into the revised production schedule. A new operator cannot simply walk onto the production line and begin working at full efficiency—they require training on the specific assembly tasks, quality standards, and safety protocols that apply to custom drinkware production. This training period can range from three to seven days depending on the complexity of the tasks and the operator's prior experience. The factory cannot commit to a revised production timeline until the operator reallocation plan is finalized and the necessary training has been completed.

The quality control sampling plan adjustment introduces an additional timeline consideration that buyers almost never anticipate when requesting quantity increases. Quality control in manufacturing is not conducted by inspecting every single unit—this would be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. Instead, factories use statistical sampling plans based on international standards such as ISO 2859-1, which specify the number of units that must be inspected based on the total lot size and the acceptable quality level. For a 5,000-unit production run, the sampling plan might require inspection of 200 units selected at random intervals throughout the production process. This sampling plan is designed to provide statistical confidence that the entire batch meets quality standards without requiring full inspection. When the quantity increases to 10,000 units, the sampling plan must be recalculated. The ISO 2859-1 standard specifies different sample sizes for different lot sizes—a 10,000-unit lot requires a larger sample size than a 5,000-unit lot to maintain the same level of statistical confidence. This larger sample size means that the quality control team must allocate more time and resources to inspection activities, which affects the overall production timeline. The factory's quality control manager must review the revised sampling plan, ensure that sufficient inspection resources are available, and adjust the production schedule to accommodate the increased inspection workload. This adjustment is not trivial—it can add two to three days to the overall timeline if the quality control team needs to bring in additional inspectors or extend inspection shifts.

The production scheduling priority recalculation creates another hidden timeline extension that buyers rarely consider when requesting quantity increases. Factories operate with finite production capacity—a specific number of production lines, a specific number of operators, and a specific number of hours available each day. When demand exceeds capacity, which is common during peak production seasons, factories must prioritize which orders receive immediate production slots and which orders are placed in a queue. This prioritization is based on a combination of factors including order size, production complexity, delivery urgency, payment status, and buyer relationship strength. A 5,000-unit order might have been assigned a specific production slot based on its original size and timeline requirements. When the buyer requests an increase to 10,000 units, the factory must reassess the order's position in the production queue. A larger order requires more production line time, which means it may no longer fit into the originally assigned production slot if other orders are scheduled immediately afterward. The factory's production scheduling team must determine whether the increased order can be accommodated by extending the existing production slot, or whether the order must be moved to a different slot later in the schedule to avoid disrupting other committed orders. This rescheduling process can add one to two weeks to the timeline if the factory is operating at high capacity utilization and cannot easily accommodate the larger order without affecting other buyers' delivery commitments.

The communication gap between factories and buyers regarding quantity tier changes stems from a fundamental difference in how each party conceptualizes production scaling. Buyers interpret production capacity as a linear function—if a factory can produce 5,000 units in 35 days, then it should be able to produce 10,000 units in 70 days, or perhaps 60 days with some efficiency gains from economies of scale. This linear model is intuitive and aligns with how buyers think about most purchasing decisions—buying twice as much of a product typically means paying twice the price and waiting twice as long. Factories, however, operate with a step-function model of production capacity. Production efficiency is optimized at specific quantity thresholds—5,000 units, 10,000 units, 20,000 units—where the production line configuration, operator allocation, and material procurement batch sizes align to minimize waste and maximize throughput. Moving from one threshold to another requires reconfiguration, which introduces a fixed timeline cost that is independent of the quantity increase itself. A factory might be able to increase production from 5,000 to 6,000 units with minimal reconfiguration, because the additional 1,000 units can be absorbed within the existing production line configuration by extending shifts slightly. But increasing from 5,000 to 10,000 units crosses a threshold that requires a complete production line rebalancing, which introduces a seven-to-fourteen-day reconfiguration window before the revised production can even begin.

For buyers who understand [how production timelines are structured](/blog/custom-drinkware-production-lead-time-new-zealand) around batch size optimization and production line balancing, the decision to finalize order quantities before requesting quotations becomes a strategic priority. Factories can provide accurate lead time estimates only when they know the exact quantity that will be produced, because the production line configuration is designed specifically for that quantity tier. Buyers who request initial quotations for 5,000 units and then later increase the order to 10,000 units introduce a reconfiguration cycle that extends the timeline beyond what either party initially expected. The factory cannot simply add the reconfiguration time to the original quoted lead time and provide an updated delivery date, because the reconfiguration affects every aspect of the production process—cycle time calculations, operator allocation, material procurement, quality control sampling, and production scheduling priority. The revised timeline must be calculated from scratch, taking into account the factory's current capacity utilization, material supplier lead times, operator availability, and quality control resource allocation. This recalculation process itself requires three to five days, during which the factory cannot commit to a firm delivery date because too many variables remain uncertain.

The quantity tier change timeline extension becomes particularly problematic when buyers are working backward from fixed launch dates or seasonal deadlines. A buyer planning a corporate gifting campaign for the December holiday season might place an initial order for 5,000 custom water bottles in September, calculating that a 35-day production timeline plus two weeks for shipping provides a comfortable buffer for unexpected delays. If the buyer's marketing team later determines that demand projections were too conservative and increases the order to 10,000 units in early October, the buyer expects the factory to simply extend the production timeline proportionally—perhaps to 60 days instead of 35 days. The buyer's mental model assumes that the October order increase still allows for delivery by late November, which provides sufficient time for distribution before the December campaign launch. The factory's reality is that the quantity increase triggers a production line rebalancing cycle that requires one to two weeks before the revised production can begin, material suppliers require an additional week to confirm availability of the increased quantities, operator reallocation requires another week for recruitment and training if additional staff are needed, and the revised production timeline is now 65 days instead of 60 days because the quality control sampling plan requires more inspection time. By the time the factory communicates the revised delivery date—mid-December instead of late November—the buyer's campaign timeline is no longer viable, and the buyer must either accept the delayed delivery or attempt to negotiate expedited production, which typically incurs premium charges and may not be feasible if the factory is operating at full capacity.

The hidden timeline cost of quantity tier changes is compounded by the fact that factories quote lead times assuming that the specified quantity is final and will not change after the quotation is accepted. When a factory provides a 35-day lead time for 5,000 units, that timeline assumes that the production line will be configured for 5,000 units, materials will be procured for 5,000 units, operators will be allocated for 5,000 units, and quality control will be planned for 5,000 units. If the buyer changes the quantity after accepting the quotation, the factory must restart the entire planning process, which introduces delays that were not accounted for in the original timeline. Buyers who finalize their quantity requirements before requesting quotations eliminate this reconfiguration cycle and receive more accurate lead time estimates. Buyers who treat initial quotations as preliminary and expect to adjust quantities later introduce uncertainty into the factory's planning process, which forces the factory to build buffer time into their quoted lead times to account for potential quantity changes. This buffer time increases the quoted lead time for all buyers, even those who do not change their quantities, because the factory cannot predict which buyers will request changes and which will not.

The material supplier batch size constraints create an additional layer of complexity that buyers rarely consider when requesting quantity increases. Material suppliers optimize their own production processes around specific batch sizes, just as factories do. A powder coating supplier might produce coating materials in batches of 5,000 portions, 10,000 portions, or 20,000 portions, with each batch size optimized for their equipment capacity and material procurement costs. When a factory orders 5,000 portions of powder coating, the supplier can fulfill the order from a single batch. When the factory increases the order to 10,000 portions, the supplier can still fulfill the order from a single batch, but the lead time might increase because the supplier must schedule a larger production run. If the factory increases the order to 7,500 portions—a quantity that falls between the supplier's standard batch sizes—the supplier must decide whether to produce a 10,000-portion batch and accept the excess inventory cost, or produce two separate batches of 5,000 portions each and accept the additional setup time cost. Either decision increases the supplier's lead time, which in turn increases the factory's material procurement timeline, which extends the overall production timeline for the buyer's order. Buyers who select order quantities that align with common material supplier batch sizes—typically multiples of 5,000 or 10,000 units—minimize these material procurement delays and receive more predictable lead times.

The operator training timeline for quantity tier changes is often underestimated by buyers who assume that factory workers can simply work faster or longer to accommodate increased quantities. In reality, production line rebalancing often requires operators to learn new task distributions and work at different stations than they did for the original quantity configuration. An operator who previously worked at the body assembly station might be reassigned to the powder coating preparation station in the reconfigured production line, because the new cycle time requirements demand a different distribution of labor across workstations. This reassignment requires training, even if the operator has general experience with powder coating processes, because each workstation has specific procedures, quality standards, and safety protocols that must be followed consistently. The training period for reassigned operators typically ranges from two to five days, depending on the complexity of the new tasks and the operator's prior experience with similar processes. The factory cannot begin production with the reconfigured line until all operators have completed their training and demonstrated proficiency in their new roles, which means the training timeline must be completed before the revised production schedule can commence. Buyers who request quantity increases during the quotation stage—before production planning has begun—eliminate this training delay, because the factory can configure the production line and allocate operators appropriately from the start. Buyers who request quantity increases after production planning has been finalized introduce a training cycle that extends the timeline by several days.

The quality control resource allocation adjustment reveals another hidden timeline cost that buyers rarely anticipate. Quality control teams in factories are staffed based on the expected inspection workload for scheduled production runs. A factory might have three quality control inspectors available during a given production period, with each inspector capable of handling the inspection requirements for multiple small orders or one large order. When a buyer increases an order quantity from 5,000 to 10,000 units, the quality control manager must assess whether the existing inspection team can handle the increased workload, or whether additional inspectors must be brought in temporarily. If additional inspectors are needed, the factory must either recruit temporary staff or reassign inspectors from other production lines, both of which introduce delays. Temporary inspectors require training on the specific quality standards and inspection procedures that apply to custom drinkware, which can take two to three days. Reassigning inspectors from other production lines may not be feasible if those lines are also operating at full capacity and cannot afford to lose inspection resources. The quality control manager must resolve these resource allocation challenges before the revised production schedule can be finalized, which adds three to five days to the overall timeline if inspector availability is constrained.

The production line changeover time between different quantity configurations introduces a final timeline consideration that buyers almost never factor into their quantity change requests. Factories typically run multiple orders on the same production line sequentially, with changeover periods between orders to reconfigure equipment, clean workstations, and prepare materials for the next order. A production line that was configured for a 5,000-unit order of stainless steel water bottles might need to be reconfigured for a 10,000-unit order of the same product, even though the product specifications have not changed. This reconfiguration is necessary because the production line balancing is different for the two quantity tiers—different cycle times, different operator allocations, different material flow patterns. The changeover time for quantity tier reconfigurations is typically shorter than the changeover time for switching between different products, because the equipment settings and quality standards remain largely the same. However, the changeover still requires two to four hours of downtime to adjust workstation layouts, redistribute tools and materials, and brief operators on the revised task distributions. This changeover time must be scheduled into the production calendar, which means the factory cannot begin the increased-quantity production immediately after completing the previous order—there must be a buffer period to allow for the reconfiguration. Buyers who finalize their order quantities before production begins eliminate this changeover delay, because the factory can configure the production line once and run the entire order without interruption.

The strategic implication for procurement teams is that order quantity decisions should be finalized before requesting production quotations, not after. Buyers who approach quantity planning as an iterative process—requesting an initial quote for 5,000 units, then adjusting to 7,500 units, then finalizing at 10,000 units—introduce multiple reconfiguration cycles that compound the timeline delays and increase the risk of missing delivery deadlines. Buyers who invest time upfront to accurately forecast demand, assess budget constraints, and determine the optimal order quantity receive more accurate lead time estimates and avoid the hidden timeline costs associated with quantity tier changes. The difference between these two approaches can be one to two weeks in the overall delivery timeline, which is often the margin between meeting a launch deadline and missing it entirely. For buyers operating in competitive markets where timing is critical—such as seasonal promotions, corporate events, or product launches—the discipline of finalizing order quantities before requesting quotations becomes a competitive advantage that directly impacts campaign success rates and customer satisfaction metrics.

The strategic implication for procurement teams is that order quantity decisions should be finalized before requesting production quotations, not after. Buyers who approach quantity planning as an iterative process—requesting an initial quote for 5,000 units, then adjusting to 7,500 units, then finalizing at 10,000 units—introduce multiple reconfiguration cycles that compound the timeline delays and increase the risk of missing delivery deadlines. Buyers who invest time upfront to accurately forecast demand, assess budget constraints, and determine the optimal order quantity receive more accurate lead time estimates and avoid the hidden timeline costs associated with quantity tier changes. The difference between these two approaches can be one to two weeks in the overall delivery timeline, which is often the margin between meeting a launch deadline and missing it entirely. For buyers operating in competitive markets where timing is critical—such as seasonal promotions, corporate events, or product launches—the discipline of finalizing order quantities before requesting quotations becomes a competitive advantage that directly impacts campaign success rates and customer satisfaction metrics.

The strategic implication for procurement teams is that order quantity decisions should be finalized before requesting production quotations, not after. Buyers who approach quantity planning as an iterative process—requesting an initial quote for 5,000 units, then adjusting to 7,500 units, then finalizing at 10,000 units—introduce multiple reconfiguration cycles that compound the timeline delays and increase the risk of missing delivery deadlines. Buyers who invest time upfront to accurately forecast demand, assess budget constraints, and determine the optimal order quantity receive more accurate lead time estimates and avoid the hidden timeline costs associated with quantity tier changes. The difference between these two approaches can be one to two weeks in the overall delivery timeline, which is often the margin between meeting a launch deadline and missing it entirely. For buyers operating in competitive markets where timing is critical—such as seasonal promotions, corporate events, or product launches—the discipline of finalizing order quantities before requesting quotations becomes a competitive advantage that directly impacts campaign success rates and customer satisfaction metrics.

The strategic implication for procurement teams is that order quantity decisions should be finalized before requesting production quotations, not after. Buyers who approach quantity planning as an iterative process—requesting an initial quote for 5,000 units, then adjusting to 7,500 units, then finalizing at 10,000 units—introduce multiple reconfiguration cycles that compound the timeline delays and increase the risk of missing delivery deadlines. Buyers who invest time upfront to accurately forecast demand, assess budget constraints, and determine the optimal order quantity receive more accurate lead time estimates and avoid the hidden timeline costs associated with quantity tier changes. The difference between these two approaches can be one to two weeks in the overall delivery timeline, which is often the margin between meeting a launch deadline and missing it entirely. For buyers operating in competitive markets where timing is critical—such as seasonal promotions, corporate events, or product launches—the discipline of finalizing order quantities before requesting quotations becomes a competitive advantage that directly impacts campaign success rates and customer satisfaction metrics.