Why Pantone Codes Don't Guarantee the Color You Expect on Custom Drinkware

Overview

Providing a Pantone code to your supplier feels like a precise specification. In reality, the same Pantone reference produces visibly different results depending on substrate material, coating method, and lighting conditions during approval.

There is a recurring pattern in custom drinkware projects that surfaces only after delivery: the buyer provides a Pantone code, the factory confirms the match, samples are approved, production proceeds—and then the delivered product appears noticeably different from what was expected. The procurement team insists the color is wrong. The factory maintains that the color meets the specified Pantone reference. Both parties are technically correct, and yet the outcome is a dispute that could have been avoided with a clearer understanding of how color verification actually works in manufacturing.

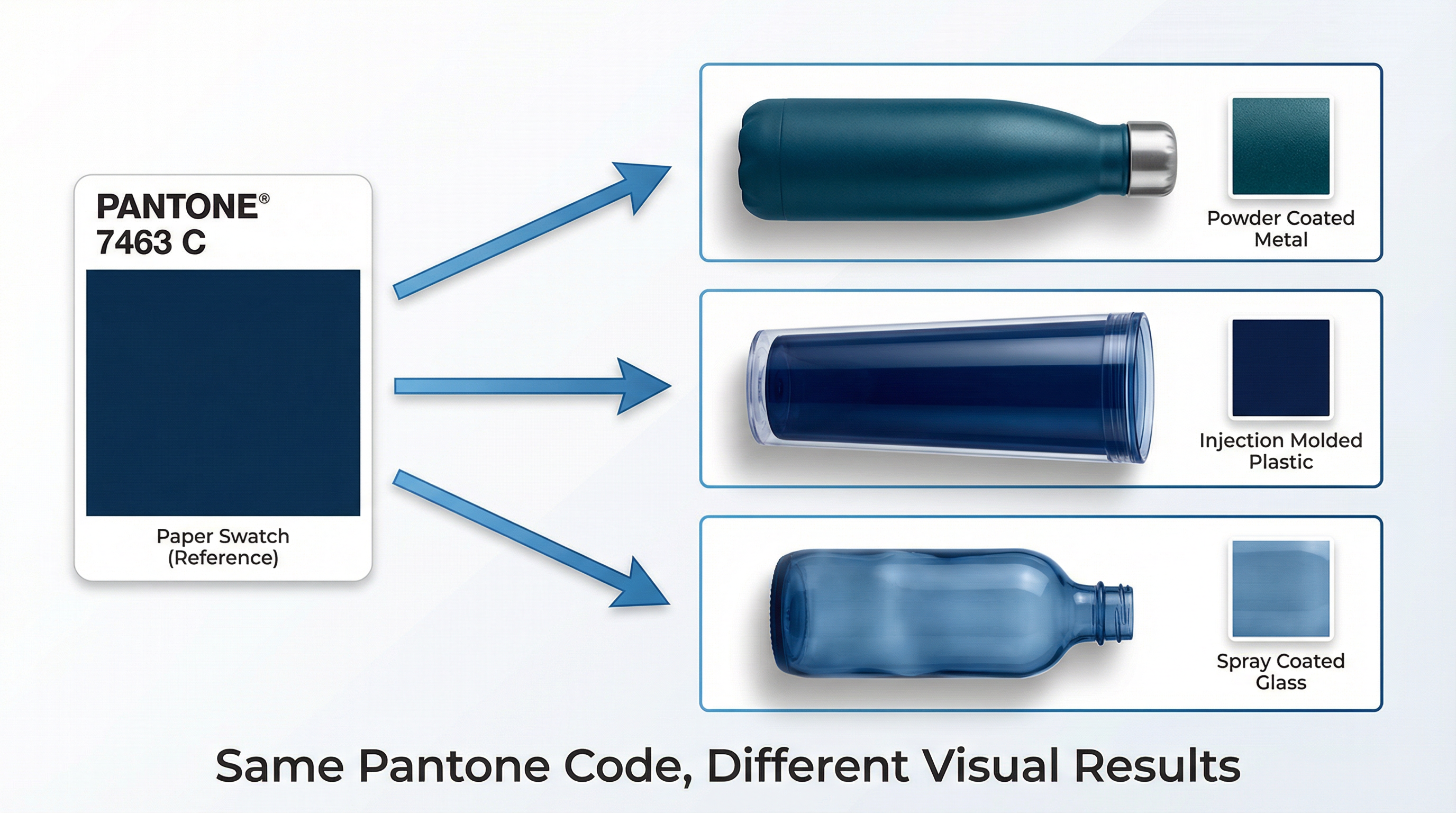

The fundamental issue is that Pantone codes are reference standards developed for printing on paper. A Pantone chip is a precisely formulated ink printed on a standardised paper substrate under controlled conditions. When a buyer specifies "Pantone 7463 C" for their custom insulated bottles, they are referencing a color that exists on a paper swatch. The factory, however, must reproduce that color on stainless steel using powder coating, or on plastic using injection molding pigments, or on glass using spray coating. These are fundamentally different substrates with different light reflection properties, surface textures, and material compositions. The same Pantone reference will produce visibly different results on each.

This is not a quality failure. It is a physical reality that most procurement teams do not encounter until their first custom drinkware project. Powder coating on metal has a different surface texture than printed paper—it may appear more matte or more glossy depending on the formulation. Plastic absorbs and reflects light differently than coated metal. Glass has a depth and translucency that paper does not. A color that appears as a rich navy blue on a Pantone chip may appear slightly greener on powder-coated stainless steel, slightly darker on injection-molded plastic, and slightly lighter on spray-coated glass. All three products technically match the Pantone reference within acceptable tolerance, yet they look different from each other and from the original swatch.

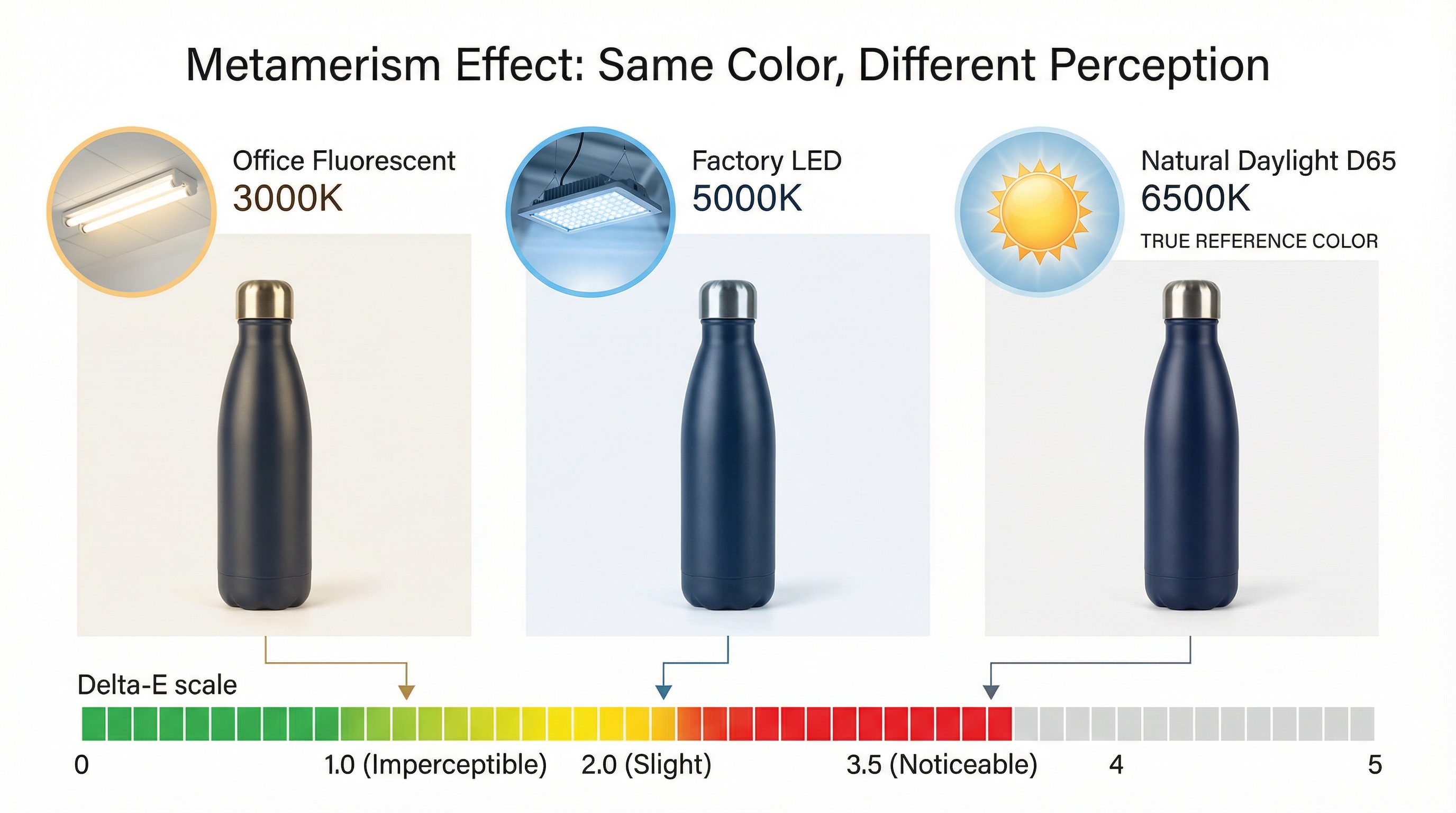

The industry standard for measuring color accuracy is Delta-E, a metric that quantifies the perceptible difference between two colors. A Delta-E value below 1.0 represents a difference that is imperceptible to the human eye. A value between 1.0 and 2.0 represents a slight difference that trained observers may notice but most people would not. A value between 2.0 and 3.5 represents a noticeable difference that may or may not be acceptable depending on the application. Most manufacturing specifications allow a Delta-E tolerance of 2.0 to 3.0, meaning that a product can be technically "within specification" while still appearing visibly different from the reference.

The second layer of complexity involves lighting conditions during sample approval. Color perception is not absolute—it changes depending on the light source under which the color is viewed. A sample approved under warm incandescent office lighting will appear different under cool fluorescent factory lighting, and different again under natural daylight. This phenomenon, known as metamerism, means that two colors that appear identical under one light source may appear noticeably different under another. If the buyer approves a sample under office lighting and the factory verifies production under industrial LED lighting, both parties may be evaluating the same color but perceiving it differently.

In practice, this is where customization process decisions begin to be misjudged. The buyer assumes that providing a Pantone code constitutes a complete and unambiguous color specification. The factory assumes that matching the Pantone code within industry-standard Delta-E tolerance constitutes acceptable quality. Neither party explicitly discusses the substrate material's effect on color appearance, the lighting conditions under which approval will occur, or the acceptable tolerance range for the specific project. The result is a gap between expectation and delivery that surfaces only when the finished products arrive.

The practical consequences extend beyond aesthetic disappointment. For corporate buyers, brand color consistency is often a compliance requirement. Marketing departments may have strict guidelines specifying exact Pantone references for all brand applications. When custom drinkware arrives in a color that appears different from other branded materials, the procurement team faces difficult questions about whether to accept the order, request rework, or negotiate a partial refund. These discussions consume time and damage supplier relationships, even when the factory has technically met the specification.

The solution is not to avoid Pantone codes—they remain the most practical way to communicate color intent across international supply chains. The solution is to understand what a Pantone code can and cannot guarantee, and to build additional verification steps into the approval process. Requesting a physical sample on the actual substrate material, rather than relying on a paper swatch, eliminates the substrate translation issue. Specifying the lighting conditions under which final approval will occur—ideally using a standardised light booth with D65 daylight simulation—eliminates the metamerism issue. Agreeing on an explicit Delta-E tolerance before production begins eliminates the ambiguity about what "matching" means.

For buyers navigating the complete customization workflow, color verification is one of several checkpoints where assumptions can create downstream problems. The sample approval stage is not simply about confirming that the product looks acceptable—it is about establishing a reference standard that both parties agree represents the target for production. If that reference standard is a paper Pantone chip viewed under uncontrolled lighting, the foundation for agreement is inherently unstable. If that reference standard is a physical sample on the production substrate, viewed under standardised lighting with an agreed Delta-E tolerance, the foundation is solid.

The gap between Pantone specification and delivered color is not a failure of manufacturing quality. It is a consequence of treating a reference standard as a production guarantee. Organisations that understand this distinction approach color verification with appropriate rigor and avoid the frustration of receiving technically compliant products that do not meet their visual expectations. Those that do not understand this distinction will continue to experience color disputes that could have been prevented with a more informed approach to the sample approval process.