Why Split International Distribution Changes MOQ Compliance Risk

Overview

How ordering at minimum quantity and splitting shipments across borders multiplies compliance exposure for custom branded drinkware.

When a procurement team orders custom stainless steel bottles or branded ceramic mugs at the supplier's minimum quantity and plans to distribute them across regional offices in different countries, the assumption is that compliance verification happens once—at production—and that the certification travels with the goods regardless of how they are subsequently shipped. This assumption holds when the entire order ships to a single destination. It breaks down when the order is split into smaller shipments crossing different borders, each subject to its own regulatory framework and each triggering separate customs scrutiny.

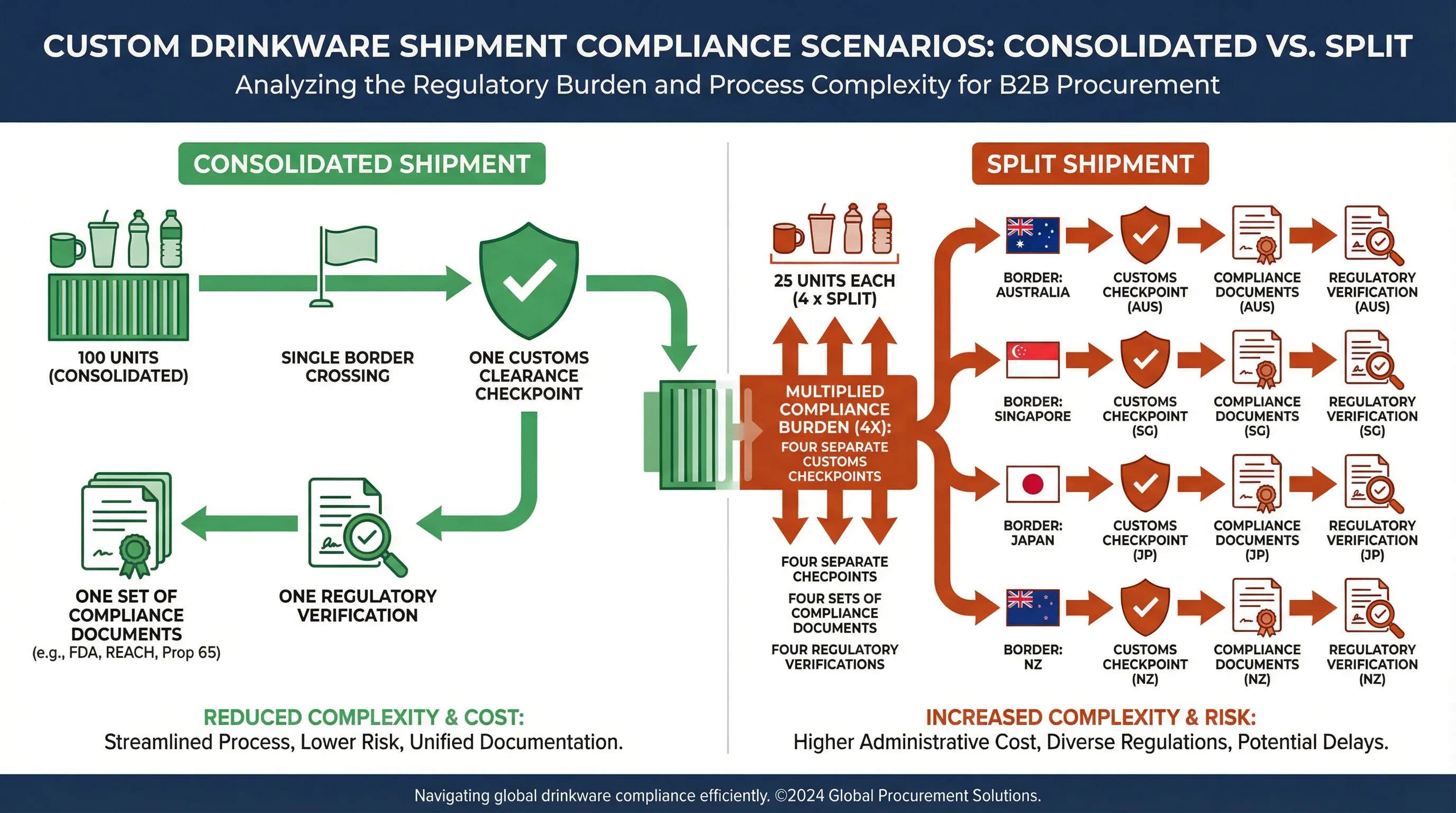

The misjudgment occurs because the relationship between order size and compliance burden is not linear. A single shipment of one hundred units crossing one border requires one set of compliance documentation and one customs clearance process. The same one hundred units split into four shipments of twenty-five units each, crossing four different borders, requires four separate compliance verifications, four customs clearances, and four opportunities for detention or rejection if documentation does not align with the specific requirements of each jurisdiction.

The Compliance Multiplication Effect

Consider a scenario where a New Zealand-based organisation orders two hundred custom insulated tumblers at the supplier's stated minimum and intends to distribute them to offices in Australia, Singapore, and Japan, with the remainder staying in New Zealand. The production facility in China prepares the order with compliance documentation appropriate for the New Zealand market—test reports for food contact safety, material declarations, and a commercial invoice listing the full order value. The shipment is then divided at the freight forwarder's warehouse into four separate consignments.

Each consignment now crosses a different border. Australia requires compliance with AS/NZS standards for food contact materials, but the documentation prepared for New Zealand may not explicitly reference the Australian standard even though the product meets it. Singapore requires a detailed packing list and may subject promotional merchandise to GST depending on declared value. Japan requires specific labeling in Japanese for any product that could be construed as food-contact, even if it is marketed as corporate merchandise. The compliance documentation prepared for the full order does not automatically adapt to these variations, and the freight forwarder is not responsible for ensuring regulatory alignment—that responsibility remains with the importer of record.

Small Shipment, High Scrutiny

The assumption that smaller shipments attract less attention from customs authorities is incorrect. In practice, low-value shipments often receive more scrutiny because they fall into categories that customs agencies associate with undervaluation or misclassification. A shipment of twenty-five branded tumblers valued at fifteen hundred dollars may trigger a detailed inspection precisely because the per-unit value seems inconsistent with typical commercial imports, or because the shipment size suggests it might be a sample rather than a commercial order, which would subject it to different duty treatment.

When customs detains a shipment for inspection, the importer must provide additional documentation to demonstrate compliance. If the original compliance reports reference the full production batch rather than the specific units in the detained shipment, or if the reports do not address the regulatory requirements of the destination country, the shipment may be held pending re-testing or additional certification. This process can take weeks and may require the involvement of a local testing laboratory, at a cost that far exceeds the value of the detained goods.

The Hidden Cost of Ordering at Minimum

The decision to order at minimum quantity makes economic sense when distribution is domestic or when the entire order ships to a single international destination. It becomes problematic when the order must be split across multiple jurisdictions, because the per-unit compliance cost increases with each additional border crossing. Understanding how quantity decisions interact with distribution strategy requires recognising that compliance is not a fixed cost absorbed at production, but a variable cost that scales with the number of regulatory boundaries the product must cross.

For organisations with multi-country distribution requirements, the alternative is to structure orders in a way that consolidates shipments to each destination rather than splitting a single minimum-quantity order. This might mean ordering above the supplier's minimum to ensure each destination receives a shipment large enough to justify dedicated compliance preparation, or it might mean coordinating timing across regions so that orders can be batched and shipped together rather than split after production. Both approaches increase the upfront order size, but they reduce the per-unit compliance burden and the risk of customs delays.

Regulatory Divergence and Product Categories

The compliance risk of split shipments varies by product category. Custom drinkware that comes into contact with food or beverages faces stricter regulatory requirements than items like branded apparel or stationery. Stainless steel bottles must meet food contact safety standards that differ between the EU, US, Australia, and Asian markets. Ceramic mugs may require lead and cadmium testing under different thresholds depending on the destination. Insulated tumblers with vacuum seals may be subject to pressure vessel regulations in some jurisdictions but not others.

When a supplier prepares compliance documentation for a production run, they typically reference the standards of the primary destination market. If the order is subsequently split and shipped to secondary markets with different standards, the documentation may not satisfy local requirements even though the product itself is compliant. Resolving this discrepancy requires either re-testing in the destination country or obtaining a compliance opinion from a local regulatory consultant, both of which add cost and delay.

Procurement Strategy for Multi-Country Distribution

The practical implication for procurement teams is that minimum order quantity decisions cannot be separated from distribution strategy. Ordering at minimum makes sense when the distribution model supports it—when goods ship to a single warehouse, or when the organisation has the infrastructure to manage multi-country compliance internally. It becomes a liability when the order must be split across borders without corresponding investment in compliance coordination.

The alternative is not necessarily to avoid split shipments, but to structure orders so that each shipment is large enough to justify dedicated compliance preparation and to ensure that the supplier is aware of the final destination markets at the time of production. This allows compliance documentation to be prepared with the correct regulatory references from the outset, rather than requiring post-production adaptation. It also ensures that each shipment is large enough to be treated as a commercial order rather than a sample, which reduces the likelihood of customs detention.

For organisations that regularly distribute branded merchandise across multiple countries, the most sustainable approach is to establish regional inventory hubs that allow for consolidated shipments to each region, with local distribution handled from within the destination market. This structure aligns order quantities with compliance requirements and reduces the per-unit cost of regulatory verification, while also improving delivery speed and reducing the risk of customs delays.