When Storage Costs Erase MOQ Savings on Custom Drinkware

Overview

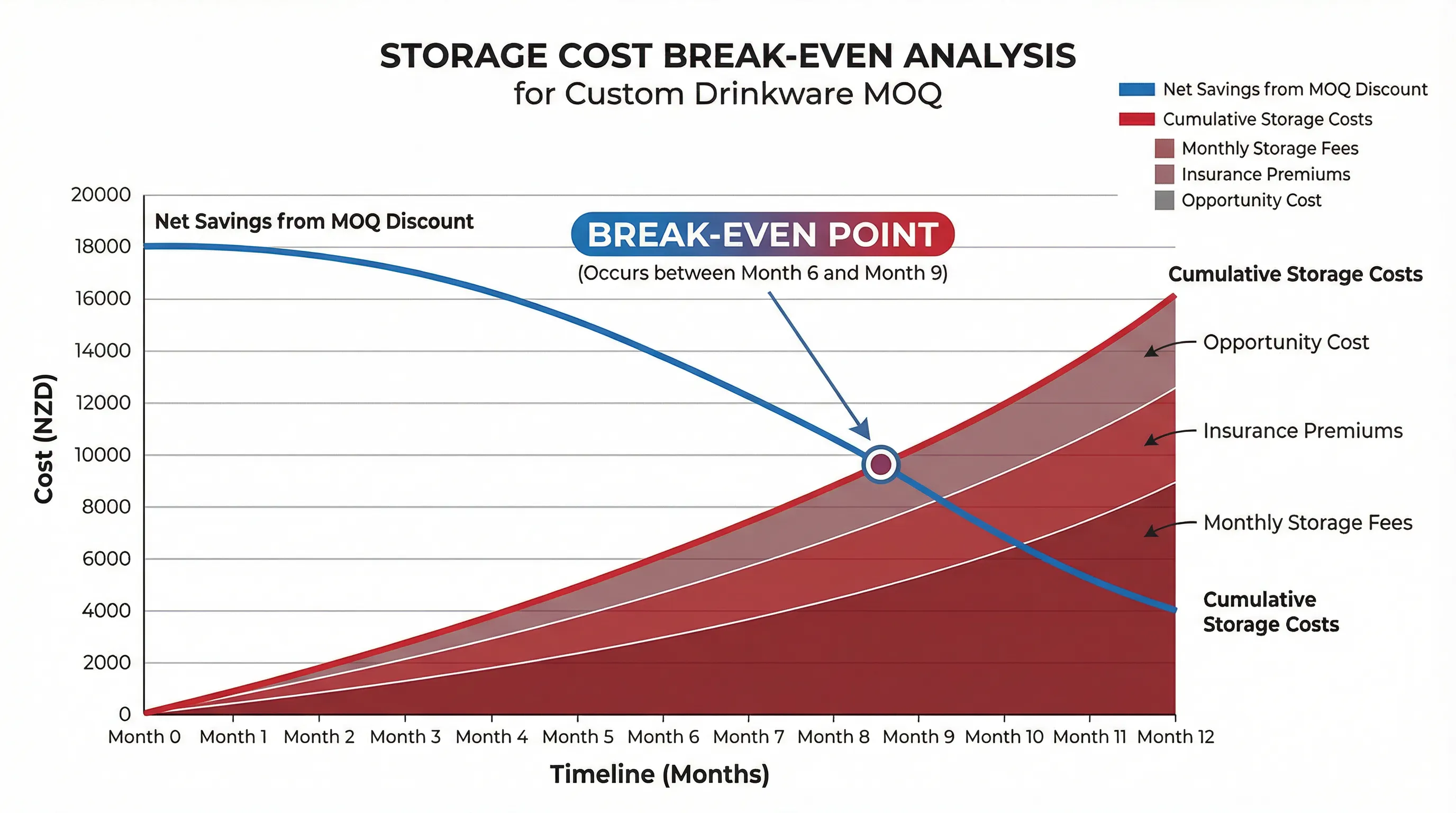

Why the per-unit advantage of ordering at minimum quantity disappears when storage duration extends beyond the break-even point. A procurement consultant's perspective.

The unit price advantage of ordering at minimum quantity disappears when storage duration extends beyond the point where cumulative holding costs exceed the per-unit discount.

When a procurement team secures a favourable per-unit price by committing to a supplier's minimum order quantity for custom stainless steel bottles or branded ceramic mugs, the immediate focus is on the savings achieved relative to ordering smaller quantities at a higher unit cost. The calculation appears straightforward: the difference between the MOQ price and the higher per-unit price for smaller orders, multiplied by the number of units, represents the value captured. This calculation is correct at the moment the order is placed. It becomes incorrect when the time required to consume the inventory extends beyond the period in which storage costs remain negligible.

The misjudgment occurs because storage costs are not static—they accumulate month by month, and for certain product categories, they accumulate faster than for others. Custom branded drinkware, particularly glass bottles and ceramic mugs, requires more storage space per unit than soft goods or flat-packed items, and it requires handling protocols that reduce the risk of breakage. These factors increase the per-unit storage cost relative to other promotional merchandise categories. When the consumption rate is slower than anticipated, the monthly storage fees compound, and at some point, the cumulative cost of holding the inventory exceeds the per-unit savings that justified ordering at minimum quantity in the first place.

The Break-Even Window

Consider a scenario where a New Zealand organisation orders three hundred custom insulated tumblers at the supplier's minimum quantity, securing a unit price of twenty-two dollars compared to twenty-eight dollars for orders below the minimum. The apparent saving is six dollars per unit, or one thousand eight hundred dollars total. The organisation's distribution plan assumes the inventory will be consumed over six months through internal events, client gifts, and new employee onboarding. The storage facility charges four hundred dollars per month for the pallet space and handling required for fragile drinkware, plus insurance at one percent of inventory value per annum.

In the first month, the cumulative storage cost is four hundred dollars. The per-unit saving of six dollars across three hundred units still represents a net benefit of one thousand four hundred dollars. By the third month, cumulative storage has reached one thousand two hundred dollars, and the net benefit has narrowed to six hundred dollars. By the sixth month, cumulative storage is two thousand four hundred dollars, and the MOQ strategy has resulted in a net loss of six hundred dollars compared to ordering smaller quantities more frequently, even before accounting for the insurance premium or the opportunity cost of capital tied up in inventory.

This break-even point—the moment at which cumulative storage costs equal the per-unit savings—varies by product category and storage arrangement, but for custom branded drinkware in New Zealand, it typically occurs between six and nine months for organisations without dedicated warehouse infrastructure. Organisations that rely on third-party logistics providers face higher per-unit storage costs due to handling fees and minimum monthly charges, which shortens the break-even window. Organisations with internal warehouse space may extend the window slightly, but they still face opportunity costs in the form of space that could be allocated to faster-moving inventory.

Product-Specific Storage Considerations

The storage cost structure for custom drinkware differs from that of other promotional products because of fragility and dimensional requirements. Stainless steel bottles can be stacked to a limited height before the risk of denting increases. Glass bottles require individual separation or protective packaging to prevent contact damage. Ceramic mugs are particularly vulnerable to chipping and must be stored in a way that minimises movement during handling. These requirements increase the cubic meterage occupied per unit, which directly increases storage fees when charged on a volumetric basis.

Insurance premiums add a secondary cost layer. Promotional merchandise is typically insured at replacement value, and for custom branded items, replacement value includes not only the unit cost but also the setup fees and artwork charges that would be incurred to reproduce the order. A three-hundred-unit order of custom tumblers valued at twenty-two dollars per unit represents six thousand six hundred dollars in replacement cost, which translates to an annual insurance premium of sixty-six dollars at one percent, or five dollars fifty per month. This cost is often overlooked in the initial MOQ calculation because it appears small relative to the per-unit savings, but it compounds over time and contributes to the erosion of the apparent advantage.

Obsolescence Risk for Branded Inventory

Custom branded drinkware carries obsolescence risk that generic inventory does not. If the organisation rebrands, updates its logo, or changes its visual identity during the period in which the inventory is being consumed, the remaining stock becomes unsellable and must be written off. This risk increases with storage duration. An order placed with a six-month consumption plan that extends to twelve months due to slower-than-expected demand doubles the exposure to obsolescence risk. The longer the inventory sits, the greater the likelihood that external factors—a merger, a market repositioning, or a regulatory change affecting branding—will render it unusable.

This risk is not hypothetical. Organisations that order at minimum quantity to capture per-unit savings often discover that the final third of the inventory remains unconsumed because the initial distribution plan did not account for changes in internal priorities, event cancellations, or shifts in employee headcount. The unsold units represent not only wasted capital but also wasted storage fees paid during the period in which the inventory was held. Understanding how order quantity decisions interact with consumption patterns requires recognising that the per-unit savings calculation is valid only if the entire order is consumed before obsolescence or storage costs exceed the discount.

Capital Opportunity Cost

The capital tied up in inventory represents an opportunity cost that is rarely factored into MOQ decisions. An organisation that commits six thousand six hundred dollars to a three-hundred-unit order of custom tumblers has deployed capital that could have been used elsewhere—whether for working capital, marketing spend, or investment in revenue-generating activities. The opportunity cost is the return that could have been earned on that capital if it had not been committed to inventory.

For organisations with tight cash flow, this opportunity cost can be significant. If the capital deployed to inventory could have generated a ten percent return over six months through other uses, the opportunity cost is three hundred thirty dollars. When added to storage fees and insurance, the total hidden cost of holding the inventory increases, and the break-even window shortens further. This calculation is particularly relevant for small and medium enterprises that operate with limited working capital and for whom inventory decisions have direct implications for liquidity.

Procurement Strategy for Storage-Sensitive Products

The practical implication for procurement teams is that minimum order quantity decisions must account for storage duration and consumption rate, not only unit price. Ordering at minimum makes sense when the consumption rate is high enough to clear the inventory within the break-even window—typically six to nine months for custom drinkware in New Zealand. It becomes a liability when consumption is slower, when storage costs are high, or when the organisation lacks dedicated warehouse infrastructure.

The alternative is to structure orders in a way that aligns quantity with realistic consumption timelines, even if this means ordering above the supplier's minimum to justify the setup cost, or negotiating staggered delivery schedules that allow the supplier to hold inventory and ship in tranches as needed. Some suppliers offer consignment arrangements where the buyer commits to a minimum quantity but takes delivery in smaller batches over time, which shifts storage costs back to the supplier while still allowing the buyer to capture the per-unit discount. This approach requires upfront negotiation and may not be available from all suppliers, but it addresses the storage cost problem without sacrificing the MOQ pricing advantage.

For organisations that regularly order custom branded merchandise, the most sustainable approach is to establish internal consumption forecasting that accounts for realistic distribution timelines, seasonal demand fluctuations, and the risk of branding changes. This allows procurement teams to make MOQ decisions based on total cost of ownership rather than unit price alone, and to structure orders in a way that minimises the risk of storage cost erosion.